The Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) has referred over 70 criminal convictions to the appeal courts in which unreliable confession evidence formed an important part of the prosecution’s case at trial.

PACE

Before the introduction of the Police and Crime Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), police interviews were rarely tape-recorded, and the rights of potentially vulnerable suspects to appropriate support were inconsistently observed.

Consequently, when a confession statement was produced in evidence which the defendant disputed or retracted, it could be difficult for the defence to challenge the police’s account.

Juries also had less awareness than they do today of the possibility of coerced or compliant false confessions.

PACE made sure police interviews were subject to clear procedural rules and were tape-recorded.

It also provided a Code of Practice that clearly defined the rights of suspects to the assistance of a solicitor and in certain cases an “appropriate adult”.

This legislation created a presumption against the admission at trial of evidence obtained through oppression or made unreliable by the circumstances of the interview.

The CCRC can investigate cases where convictions were based on disputed confession evidence.

Sometimes, this evidence has been obtained at the end of intensive police questioning.

In many cases, particularly those which have involved young or vulnerable suspects, confessions were made in circumstances in which the defendant had been unreasonably denied access to solicitors, parents, or other appropriate adults.

Forensic Evidence

Part of the CCRC’s referral in the well-known case of Derek Bentley was forensic analysis indicating that an alleged confession statement, claimed by the prosecution to represent a verbatim record, had in fact been edited by police officers. The Court of Appeal posthumously quashed Mr Bentley’s murder conviction.

Derek Bentley’s conviction was referred by the CCRC in 1997

Similar methods of expert forensic analysis were used in the murder cases of Reginald Dudley, Robert Maynard and Kathleen Bailey.

The defendants had been convicted in part on disputed confession evidence. The senior investigating police officer had made a full verbatim written (rather than tape-recorded) record of the interviews, but the defendants claimed these records had been falsified.

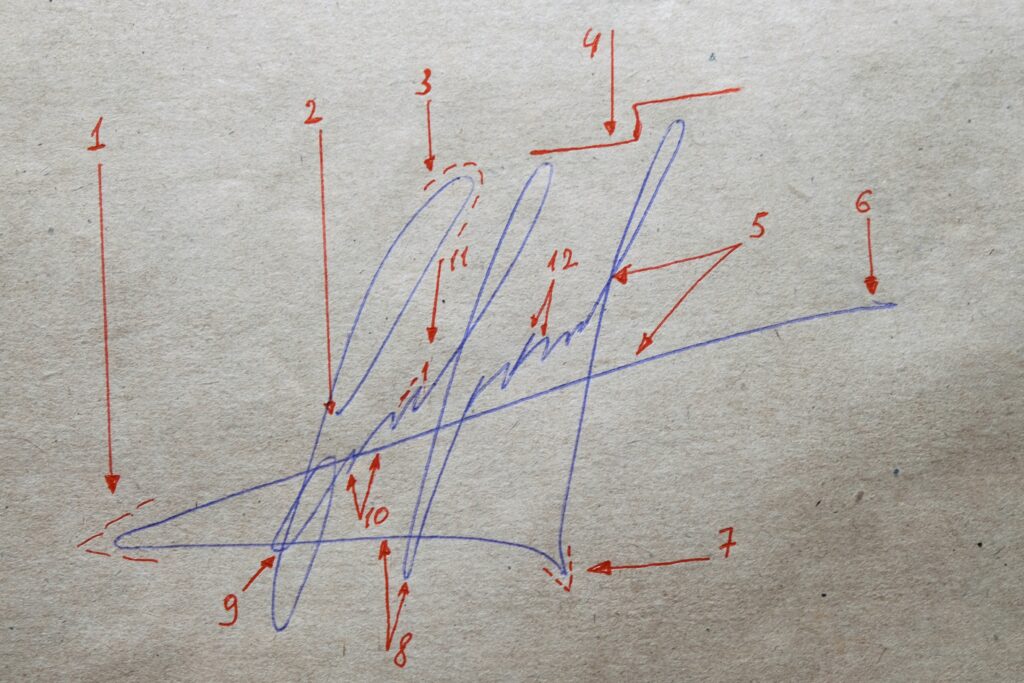

In its review of the convictions, the CCRC obtained new expert handwriting evidence indicating that it would have been impossible for any person to have written a verbatim account of those interviews over the time the interviews were said to have lasted.

Similarly, in the case of Robert Brown, convicted of murder in 1977, Mr Brown alleged that a confession which had not been tape-recorded had never actually been made but had been written by police officers. The police officers had stated that the confession was dictated by Mr Brown.

The CCRC’s referral was partly based on new expert linguistic analysis which concluded that the confession statement had been produced by a process of question and answer before being converted into a monologue. This undermined the police’s account of the interview.

In many cases, the forensic technique used has been an “electrostatic detection device” (EDD).

EDD is specialised equipment used for document examination which reveals indentations or impressions in paper that might otherwise go unnoticed.

In the case of Peter Tredget, for example, EDD evidence found that confession statements had not in fact been recorded in the way described under oath by the interviewing police officer, namely that they were contemporaneous, dictated records.

Psychiatric Evidence and Vulnerable Suspects

Psychiatric material is another kind of expert evidence that has been used in the CCRC’s reviews of cases involving disputed confessions.

Sometimes this has been used to show that a defendant was suffering from specific psychiatric or psychological vulnerabilities which made them compliant or open to manipulation during interview.

This type of evidence can cast doubt upon the reliability of a confession, as in the cases of Donald Pendleton, Geoffrey Foster, and Patrick Nolan.

In Mr Pendleton’s case, he was interviewed 11 times over three days without a solicitor before confessing to a murder. A CCRC review found new evidence of vulnerability indicating the confession was not reliable.

Intensive interrogation without the presence of solicitors was also a common theme in the joint convictions of Ellis Sherwood, Michael O’Brien and Darren Hall.

The CCRC found that Mr Hall, who had made a confession which he retracted after the trial, had been interviewed nine times over 48 hours despite his vulnerabilities making him an unreliable witness.

In this case, there had also been breaches of PACE in that the defendants had been denied access to solicitors for most of the time they were in custody and there was evidence they had been interviewed “off the record” on multiple occasions.

Another example is the 1953 murder conviction of Iain Hay Gordon. On the law as it then stood, Mr Hay Gordon was found “guilty but insane,” principally on confession evidence.

The CCRC considered that this confession had been obtained at the end of a police interrogation in which an officer had used Mr Hay Gordon’s homosexuality, which was then illegal, to pressure him to confess. The conviction was later quashed by the Court of Appeal.

Northern Ireland and Youth Confessions

Young people are a category of vulnerable defendant that have featured in many of the CCRC’s reviews, particularly in its referrals of Northern Ireland convictions.

Many of these convictions were secured in the legal and political context of “The Troubles”.

Examples include the cases of Patrick Thompson, Eamonn MacDermott, Peter McDonald, and Joseph Fitzpatrick.

In these cases, some common themes included:

- Long and intensive questioning leading up to a confession

- Prolonged periods of detention in custody

- A failure to assess suspects for their fitness for interview

- Denials of solicitors or appropriate supporting adults to suspects

- Allegations of mistreatment during detention and interrogation

- New EDD evidence revealing that interview records had been rewritten

These convictions were later quashed by the Northern Ireland Court of Appeal.

We will be publishing a more in-depth look at our Northern Ireland cases soon.

Breach of PACE

The CCRC has reviewed other cases in which there had been failures to adhere to PACE’s Code of Practice.

Referrals have resulted in cases where the CCRC’s review found that breaches of the Code of Practice had caused substantial unfairness to the applicant.

For example, the CCRC has referred the convictions of 16 defendants whose cases involved officers from West Midlands Police’s “Serious Crime Squad” in the early 1980s.

Several officers from this squad were later found to have fabricated confessions and evidence, and to have engaged in other misconduct.

In the case of Alexander Allan, for example, the CCRC found numerous breaches of PACE during the interviews which led to a confession that was disputed by Mr Allan.

Issues included:

- Mr Allan was not cautioned on arrest or before questioning

- A record of the interview was not made as soon as practicable after the interview and the record was not timestamped or signed

- No opportunity was provided to Mr Allan to read or sign the “Record of Admission”

Following a referral of Mr Allan’s conviction in 1998, the Court of Appeal overturned it.

You can find a list of all the CCRC’s referrals that have involved disputed and/or unreliable confession evidence.

The CCRC continues to review cases which feature disputed and/or unreliable confession evidence. If our investigation finds that there is a “real possibility” the appeal court will quash the conviction, the CCRC can refer it.

If you believe you have been the victim of a miscarriage of justice, you can contact the CCRC for a free review of your case.