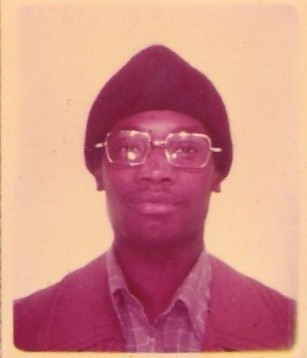

Winston Trew was one of the “Oval Four” – four black men arrested by police at Oval Station on the London Underground on 16 March 1972 and falsely accused of stealing passengers’ handbags. He and his co-defendants, Stirling Christie, George Griffiths and Constantine “Omar” Boucher, were all aged between 19 and 23 when arrested. They were of Jamaican origin and had moved to the UK as children.

They were arrested by a special patrol set up to target thefts on the Northern Line led by the discredited and corrupt British Transport Police officer DS Derek Ridgewell.

You can find the CCRC’s Case Study on DS Ridgewell here. It takes a look at the 13 historic convictions referred to the Court of Appeal by the CCRC on the basis of new information relating to the misconduct of DS Ridgewell and his colleagues.

Here Winston Trew provides an account in his own words of the circumstances that led to his arrest and conviction, and the road to eventually clearing his and his co-defendants’ names at the Court of Appeal.

How it all began

On 16 March 1972, I and three friends were on our way home from a meeting in North London when we were confronted by a group of six men and one woman at the Oval underground station.

Claiming to be police, we asked them for identification but they accused of “nicking handbags”. Outraged, we denied this and insisted they identify themselves, but they refused and began pushing us against a wall.

As we were all members of a black community organisation and knew our rights, we insisted that they must identify themselves. Following an argument and a bout of pushing and shoving, a fight broke out between us four and the group of seven.

We were eventually overpowered and it was only then that I found out that the group were actually undercover detectives from the British Transport Police’s (BTP) so-called “anti-mugging squad,” set up to catch thieves and pickpockets on the London underground.

During the scuffle, one of our number fled from the unprovoked attack but was caught and taken to the same police station as the three of us.

Once in the local police station, as nothing incriminating was found in our possession, the accusations changed from “nicking handbags” to attempted theft and assault on police. DS Ridgewell and other detectives set about applying threats and violence to get me to sign a self-incriminating statement, to which I initially refused.

The following morning at Camberwell Magistrates’ Court, I faced up to 17 charges, from attempted theft to assault on police that occurred at the Oval station.

I had admitted to the theft and robbery charges in a signed statement procured by the threats and violence at the police station, even though I knew this admission was false.

Trial at the Old Bailey and the appeal

Following a five-week trial, I and my three friends were found not guilty of all the counts of robbery and theft from persons unknown to which I admitted in the police station. This was because I had a cast-iron alibi for all dates on which I allegedly committed the crimes.

To my horror, however, I was found guilty on two counts of attempted theft from persons unknown and two counts of assault on police at the Oval underground, to which the police were the only witnesses.

I and my two friends were given two years in prison for each count and the youngest was given two years’ detention in Borstal. I actually thought that I was given eight years in prison for the four counts until my solicitor explained that they were concurrent sentences.

Immediately, the world that I knew crashed as I was convicted and imprisoned for crimes that I did not commit. I appealed.

At the Court of Appeal in July 1973, new evidence that cast doubt on the theft of the police woman’s handbag during the fight, which would have undermined the whole police case, was rejected, and my convictions were upheld. Lord Justice James, however, cut the two year sentences to 12 months and ordered my release from prison the following day.

Dissatisfied with my wrongful convictions, I spent the next four decades determined to right a wrong, and began this by collecting all the press reports on the case and on DS Ridgewell.

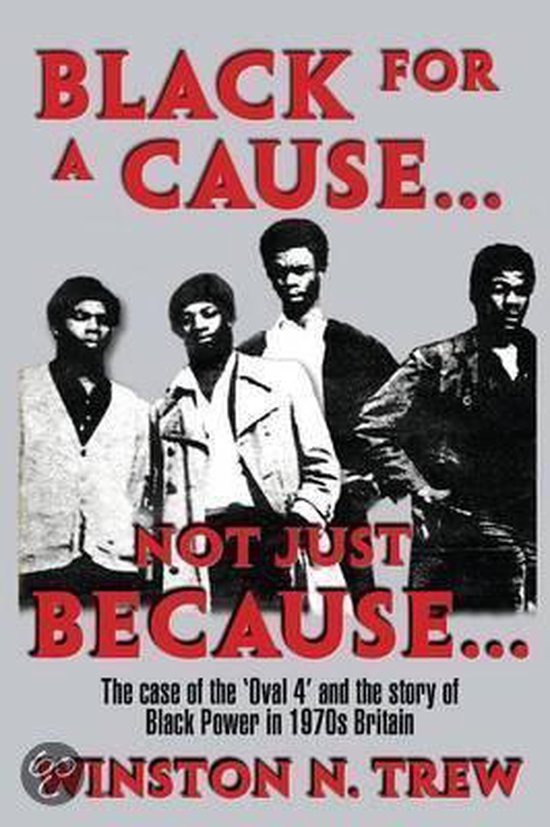

I read books on the 1972 “mugging scare” and began researching DS Ridgewell’s past by using the Freedom of Information Act. This research was published in a book, Black for a Cause, in 2010.

The Stephen Simmons appeal

Unbeknown to me was that in 1975, DS Ridgewell arrested three innocent young white men for mailbag theft from Clapham railway depot. On Ridgewell’s evidence, they were all found guilty and given two years’ detention in Borstal.

In 2013 one of the men, Stephen Simmons, dissatisfied with his wrongful conviction, phoned a radio programme and told the sitting barrister about his wrongful conviction. He was advised to do an internet search on the officer.

He did so and to his shock found that Ridgewell had been convicted of the very offence for which he had been convicted. He then came across my book with information not only on Ridgewell but on the four cases of black men he had fitted-up on the London Underground using perjury, false evidence and violence.

With this new evidence, he applied to the CCRC to have his case reviewed. During that review, the CCRC got in touch with me in January 2017 for further information on Ridgewell, which I sent.

This information included a DVD of the July 1973 BBC programme, Cause for Concern, which investigated Ridgewell’s malfeasance against the “Waterloo Four,” the “Stockwell Six,” the “Oval Four,” and the “Tottenham Court Two” on the London Underground.

In August 2017, the CCRC referred Stephen Simmons’ case to the Court of Appeal and in January 2018 his conviction was quashed by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Burnett.

Th CCRC’s investigation

With Simmons’ victory as my new evidence, I applied to the CCRC in February 2018 and sent to them all the information I’d collected on Ridgewell over four decades. Also sent to my case officer were indictments from the National Archives on the Stockwell Six, the Tottenham Court Road Two and the Oval Four.

With the widespread publicity from Stephen’s victory, I was directed by crime reporter Duncan Campbell to a retired ex-superintendent of the BTP, Graham Satchwell, for any information on Ridgewell. Subsequently, Mr Satchwell gave the CCRC a written statement about Ridgewell’s reputation and the culture within the force at the time.

The CCRC made it plain to him that without the relevant case papers the appeal might fail. The CCRC had used their powers under Section 17 of the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 to request any documents held by the BTP on the Oval Four case, but were told they did not exist.

Strangely, however, during his research for a book on the Great Train Robbery, Mr Satchwell came across seven volumes of the transcript of the original trial at the Old Bailey which had been wrongly stored. He informed me and my case officer and the BTP were compelled to hand over those documents.

With these documents, my case officer was able to build a solid case. The CCRC also found that due to the age of the case most court documents had been destroyed. Further searches did, however, locate other information on Ridgewell’s practice of using of false confessions to convict.

Finally, it is fair to say all the available information that I had collected on Ridgewell over the decades had no legal meaning until they were put together in a narrative of Ridgewell’s corruption by my case officer.

Importantly, the CCRC applied new legal arguments which enabled suspicions of Ridgewell’s past wrong-doings – refused in my 1973 appeal – to be admitted in my renewed appeal in 2019.

The new evidence and new argument

The new evidence presented to the court by the CCRC on my behalf was, firstly, the successful appeal of Stephen Simmons in January 2018. This was based on the fact that Ridgewell had been convicted of corruption in 1980 and jailed for seven years at the Old Bailey. He was convicted for organising what was called a “massive scale of thefts” from the Bricklayers Arms goods depot in collaboration with local criminals.

Secondly, supporting evidence was submitted that my convictions followed a pattern of false evidence, perjury and violence by DS Ridgewell and his team to force confessions of guilt from up to sixteen innocent black men on the London Underground over two years.

Thirdly and, importantly, the CCRC submitted observations on the infectious role of perjury in previous “London Underground” cases.

Against that background of new evidence and legal precedent, Lord Burnett sitting with Mrs Justice McGowan DBE and Sir Roderick Evans held that the police evidence in our case was tainted and that convictions based on such testimony could, therefore, not stand. The Court quashed all the convictions.

Success at the Court of Appeal

Following my victory on 5 December 2019, I told reporters outside the Court of Appeal that Ridgewell was convicted and imprisoned for stealing mailbags, but in my case he had wilfully and maliciously stolen nearly 50 years of my life, and I would never them get back.

At the hearing I congratulated my case officer via my defence counsel, Judy Khan QC, for putting together an excellent Statement of Reasons on a dated and complex case. The Lord Chief Justice agreed and added that “We would wish only to note our regret that it has taken so long for this injustice to be remedied”.

I can safely say that had it not been for the work of my case officer at the CCRC in putting together and submitting an excellent of Statement of Reasons to the Court of Appeal, my convictions may well not have been overturned.

The role of the CCRC is not just necessary but vital to overturning miscarriages of justice.

You can find the CCRC’s Case Study on DS Ridgewell here.

You can also find a list of all referrals the CCRC has made concerning DS Ridgewell in our Case Library.

Anyone else who believes they might be a victim of a miscarriage of justice, convicted in a case involving Derek Ridgewell, is urged to contact the CCRC. If our review finds that there is a “real possibility” the appeal court will quash the conviction, the CCRC can refer it.